In a timely conversation hosted by the Rajawali Foundation Institute for Asia and co-sponsored by the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Steve Yates, Senior Fellow at the Heritage Foundation and former deputy national security advisor, joined Tony Saich and Edward Cunningham to examine how strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific is reshaping alliances, economic policy, and the regional security order. Rather than treating Asia’s current turbulence as a short-term disruption, the speakers explored a deeper shift: a move from the familiar logic of US offshore balancing toward more flexible, issue-specific coalition building, with Taiwan increasingly central to the region’s strategic calculations.

Edward Cunningham opened by situating the discussion in a broader pattern of change. Economic and security architectures that once moved in parallel are now being rewired at the same time. Industrial policy, export controls, and supply-chain “de-risking” are creating overlapping geoeconomic blocs, while security cooperation is increasingly organized through “mini-lateral” groupings and ad hoc coordination. In this more layered environment, the question is not whether the United States remains engaged, but how it engages and how partners in Asia interpret the demands and opportunities of a new strategic landscape.

Global Shift

Steve Yates began with a methodological caution: debates about U.S. foreign policy can become overly personality-driven, obscuring structural change. He urged the audience to distinguish perception from reality and to ask what has actually shifted in the assumptions guiding state behavior.

His argument was that the world is entering a “post-globalist” moment – a period in which major powers and regional actors place less faith in the idea that global institutions, norms, and deep economic interdependence will reliably constrain geopolitical competition. In this framing, the goal is not to discard institutions outright, but to recognize their limits and to build strategies that can function when institutions stall, dilute accountability, or fail to deter coercion.

International Relations ‘stress tests’

To illustrate why confidence in the Bretton Woods system has weakened, Yates pointed to several recent stress tests that exposed institutional limits, in his view.

- Ukraine and the credibility of security assurances: Yates argued that the war underscored how quickly security guarantees can be tested and how difficult it can be for international mechanisms to prevent escalation once a major power chooses force.

- The UN Security Council’s constraints: he used the Ukraine crisis to highlight how the Council’s structure can paralyze collective action when a permanent member is directly implicated.

- Pandemic-era governance and coordination failures: Yates described COVID-19 as another stress test, suggesting that global coordination and accountability mechanisms struggled under political pressure and competing incentives.

These examples served a broader point: when institutional guardrails look unreliable, states hedge. They invest more in resilience, supply-chain redundancy, and coalitions of trusted partners that can act even when universal institutions cannot.

Coalition building in practice: burden-sharing, standards, and deterrence

Yates did not present this shift as isolationism. He argued that the current period has been marked by active engagement – intensive diplomacy, leader-level visits, and persistent regional travel – but with a different emphasis: aligning allies and partners around shared burdens and shared rules rather than assuming U.S. primacy will automatically translate into coherent collective action.

He offered Europe as a cautionary parallel: even among close partners, economic choices can diverge from security priorities. He pointed to debates about energy dependence, asymmetrical military financial burdens borne largely by the US, and the uneven pace of strategic adjustment as evidence that coalition management is now central to American statecraft.

In Asia, his emphasis was on momentum: when coercion increases, coordination tends to follow. Yates highlighted Japan’s long trajectory toward a larger security role and used the Philippines as an example where perceived external pressure helped catalyze renewed defense cooperation and maritime coordination. In his telling, regional actors are not merely responding to U.S. signals; they are responding to lived incentives and rising perceived risks.

Yates also argued that the next phase of coalition building will be shaped as much by technology governance as by traditional force posture. He urged a greater focus on standard-setting and trusted ecosystems – floating the idea of a ‘T7’ (a technology-focused coalition) as a complement or corrective to legacy groupings. The ambition is to define rules, interoperability, and accountability in frontier domains, rather than to chase every move by competitors.

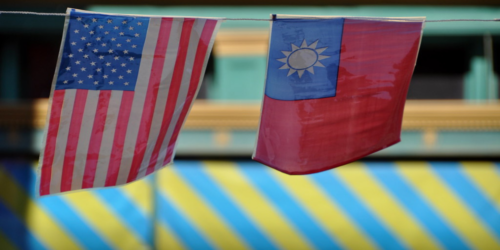

Why Taiwan sits at the center

The conversation returned repeatedly to Taiwan – not only as a political flashpoint, but as a focal point for coalition logic. Saich laid out moral, strategic, and economic arguments for Taiwan’s significance, emphasizing that the economic and navigation case is often the most persuasive in practice. In parallel, Yates stressed that Taiwan Strait stability has regional stakes that extend well beyond Taiwan itself, shaping the calculations of Japan and others.

Yates’ supply-chain point was blunt: crisis-critical dependencies that approach “100%” are hard to defend in a world of coercion and contested logistics. That reality, he argued, is driving de-risking debates that aim not for “zero” exposure but for resilient alternatives and diversified capacity. This is where geoeconomics and security converge: the credibility of deterrence increasingly depends on whether societies can absorb shocks, sustain essential production, and maintain political cohesion under pressure.

Resilience, trust, and the politics of credibility

Audience questions pushed the discussion toward credibility and readiness. Saich raised the problem of confidence in U.S. leadership and asked why international trust remains thin when Washington’s strategy seems clear to insiders. Yates pointed to the information environment and the way slogans and headlines travel across borders, often stripped of context.

On Taiwan’s readiness, Yates emphasized “civil resilience” as a whole-of-society capability: infrastructure hardening, emergency preparedness, communications continuity, and practiced coordination. He argued these capacities should be treated as part of deterrence, not as an afterthought. He also noted that democratic politics can lag public seriousness – but that resilience investments, once made, change the strategic picture by reducing opportunities for coercion.

Key takeaways

- Coalition building is becoming the organizing principle: not a single bloc, but flexible networks aligned around shared risks, rules, and capabilities.

- Geoeconomics and security are now inseparable: supply chains, industrial policy, and standards-setting increasingly function as strategic tools.

- Taiwan’s centrality is both strategic and economic: deterrence debates hinge on navigation, technology ecosystems, and the resilience of democratic societies.

- Credibility depends on readiness and communication: civil resilience and political cohesion matter as much as hardware, and trust is shaped by the global information environment.

Watch the full conversation here.