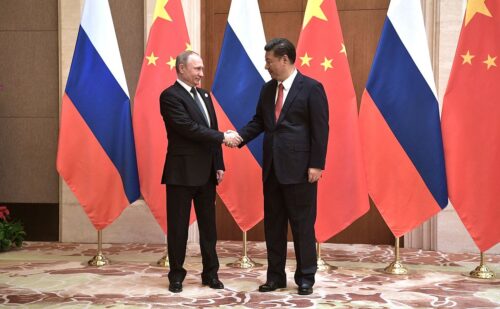

Nearly a year after launching its ill-fated invasion of Ukraine, Russia finds itself politically and economically adrift, and increasingly dependent on China as a key diplomatic lifeline. Vladimir Putin’s gambit in Ukraine, however, has nonetheless generated unease in Beijing and is testing the limits of the Russo-Sino partnership according to Tony Saich, a longtime China watcher who leads the Kennedy School’s Rajawali Foundation Institute for Asia director and has written extensively on China’s politics and leadership.

Speaking with Alexandra Varcroux, the executive director of Harvard’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies during a conversation moderated by PBS Frontline Editor-in-Chief Raney Aronson-Rath, Saich painted a picture of China pivoting closer to Moscow as a counterweight to the United States, but also wary of becoming overly entangled in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

“Ultimately, Xi Jinping and the Chinese leadership have come to the conclusion that the long-term problem for them is the United States, and that’s where there’s going to be confrontation over a longer period of time,” Saich said. “Well, under those circumstances, what better situation could you have than a huge partner on your border that can offer you energy? It can offer you oil, it can offer you liquefied natural gas. It has minerals.”

While China has lent important diplomatic and economic cover to Russia over the past year, that support has been far from unconditional, Saich explained. “They’ve been careful not to alienate the West too much,” he said. “So, they’ve been careful not to get involved in activities that would bring U.S. and Western sanctions on them.”

Beijing was also quick to pour water on Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling as it faced a costlier, bloodier, and more protracted conflict. “The one area where they did intervene was to say pretty clearly and pretty loudly, ‘No, the use of nuclear weapons, is clearly not acceptable,’” Saich said.

Though Beijing may see Moscow as an important counterweight to the United States, it is far from an alliance of equals, explained the Davis Center’s Vacroux: “This relationship right now is much more important for Putin than it is for Xi. … For Putin, Xi is the lifeline given how much Russia has been cut off from Europe since the war began.”

China may be lending its rhetorical support to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it comes at a price, as Chinese energy buyers are also winning deep concessions on oil and gas sales as Western markets have largely been closed off to Russian exports, Vacroux said. “There’s definitely a benefit to China from having Russia on the back foot,” she added.

Ultimately, this relationship between Moscow and Beijing is a “marriage of convenience” Vacroux argued, with Russia being the junior partner in the relationship. “It’s good for both of them now, but they don’t really trust each other,” she said, Reminding the audience of the intense Cold War-era rivalry between the Soviet Union and China to claim the vanguard of the communist revolutionary mantle. The two countries even traded military blows during a series of border skirmishes in the late 1960s.

While Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine has brought these onetime rivals closer together, perhaps the more important question is what this portends for a future multipolar world where U.S. dominance no longer goes unchallenged. “When it comes to the United States,” noted Vacroux, “one of the things that’s always fascinated me is that because of the history of both being superpowers, the Russians would really like us to worry about them as much as they worry about us. And they just can’t believe that Americans don’t think about Russia every day the way that Russians think about the United States and NATO every day.”

Yet for the United States, a newly belligerent Russia under Putin represents a minimal threat to its military and political leadership of the international community. Referencing the Biden administration’s newly released national security strategy, “Russia’s a short-term problem,” noted Saich. “The real problem long-term is China.”