Essay

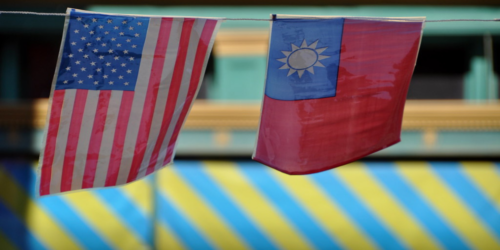

From Balancing to Coalition-Building: The US, Taiwan, and Asia’s Grand Reshuffling—Event in Review

A summary of the event, co-hosted by the Rajawali Foundation Institute of Asia and the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

Feature

The Ash Center and Rajawali Foundation’s discussion on the Indo-Pacific focused on the evolving geopolitical dynamics between the U.S., China, and Taiwan, highlighting the complexity of Taiwan’s political identity and its strategic importance in regional security.

At a time of shifting global alliances and heightened geopolitical uncertainty, the Indo-Pacific remains a focal point of 21st-century international relations and power dynamics. To unpack these complex issues, the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation hosted a discussion featuring Kira Coffey, an Air Force National Defense Fellow and research fellow at the Belfer Center at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS); Rana Mitter, a historian and S.T. Lee Chair in U.S.-Asia Relations at HKS; and moderator Edward Cunningham, director of China Programs at the Ash Center and the Asia Energy and Sustainability Initiative at HKS.

The conversation centered on the evolving relationships among the United States, China, and Taiwan and how these shifts could reshape regional security architecture, trade patterns, and diplomatic alignments. As Cunningham observed in his opening remarks, “The question is not whether things will evolve and tensions will increase, but how.”

Contested Histories and Current Tensions

The United States, China, and other Indo-Pacific powers share a long and complicated history that continues to shape present-day strategic and political decisions. Indeed, Mitter noted that both Beijing and Taipei often present overly simplified historical narratives, either asserting Taiwan’s inextricable connection to the mainland or emphasizing that it’s entirely separate. But the island’s history is more nuanced, shaped by over 125 years of shifting governance and evolving political identity. “The political salience of Taiwan continues to be something that can be moved up and down—by factors other than China as well—but China has a lot of capacity to control the political language around the Taiwan issue,” said Mitter. Coffey added that “Taiwan in particular is very much [a question] of national identity between the Chinese on both sides, and the further we go, the more of a divergence we’re seeing.”

Recalibrating U.S. Engagement

Despite concerns that recent cuts to U.S. embassies and consulates signal disengagement, both Coffey and Mitter argued that the Indo-Pacific remains central to U.S. foreign policy. “From a pragmatic perspective … it makes a lot of sense,” Coffey said. “If competing with China is the priority, we can’t just say it’s the priority—we need to operationalize that priority.” Additionally, Mitter cited recent comments from Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth as offering “clear and unequivocal statements about the continuing value the United States sees in maintaining a strong security presence in the region.”

Going Beyond Deterrence

There was consensus among the panelists that military deterrence remains important but insufficient, with Coffey emphasizing the need for a broader, more tailored approach that meets regional partners where they are. “Seventy-five percent of Pacific Island nations don’t have militaries,” she noted, requiring the United States to think about security at the level of law enforcement, information sharing, and civil infrastructure.

Coffey also called for better U.S. strategic messaging. While the United States often outpaces China in foreign direct investment, it struggles to advertise this support. “We do a lot, but we don’t take ownership or pride in it,” she said. “We like to communicate that we compete on values,” but for many partners, the priority is clean water, roads, and working governance—and China is more visibly delivering on those fronts.

Strategic Ambiguity

A central theme of the conversation was the role of strategic ambiguity around Taiwan, which has long allowed the United States to avoid overt conflict in the region and balance intrinsic and extrinsic interests without committing to a specific response. “The politicians on all sides are trying to find ways to see what a stable region, with Taiwan very much at the center of it, might actually look like,” Mitter observed. While the liberal international order favors maintaining the status quo, China continues to push for change, with Taiwan under its control.

So, Cunningham asked, what might be some markers that the current trajectory is shifting? Mitter pointed to developments in international trade, such as how disputes or settlements might impact Taiwan’s positioning. He also cited Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) accession efforts, with both Taiwan and China being interested, but for different reasons, as a key space to watch for signs of changing alignments.

At the same time, Mitter emphasized that a violent takeover of Taiwan would run counter to Beijing’s long-term interests. While such a move might be celebrated domestically as a “glorious victory,” it would damage China’s image in the region. “The story that actually would spread,” he said, “is that China was unable to peacefully persuade supposed compatriots to rejoin with the mainland.” In contrast, China’s current geoeconomic strategy positions it as a “stabilizing regional hegemon.”

Coffey suggested watching how the ongoing tariff war unfolds. While many focus on the idea of a planned Chinese military operation around 2027 (the year Xi Jinping has reportedly told his military to be ready), there’s another possibility that economic turmoil or internal political pressure could push Xi to act more rashly. “If his back is against the wall,” she said, “he may have to do something to cement his legacy.” In that case, Taiwan might face conflict under less predictable conditions that could work in its favor. “We often talk about slowing down the clock for China,” she added, “but the best way to slow them down is to force them to speed up. They can’t be as methodical when they’re rushed.”

The Gray Zone and the Bigger Picture

Additionally, Coffey warned against focusing too narrowly on overt military action. Between peace and kinetic conflict, she explained, lies what the United States calls the “gray zone,” but a space China refers to as “unrestricted warfare.” While the United States is distracted by “saber-rattling,” she said, China quietly advances through “coercion, cognitive warfare, and other malign activities to increase its presence … [and] influence, one salami slice at a time.”

In this space, Taiwan’s most effective defense may be societal. Coffey emphasized that China is no longer trying to win the people of Taiwan over to their side; rather, it’s trying to divide them. Therefore, combatting the information and psychological domains may offer the “most bang for your buck.” Mitter agreed, adding that domestic polarization, driven by housing affordability as much as geopolitics, is as much a risk as China: “The resilience of whole-of-society efforts … only really end up being effective in a society that believes that it is genuinely united in some beliefs about its identity and what direction of travel it wants to go in.”

Essay

A summary of the event, co-hosted by the Rajawali Foundation Institute of Asia and the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

Video

As a new administration takes shape in Washington, join us for a timely discussion exploring the complex dynamics shaping the Indo-Pacific region. We will examine critical questions facing U.S.-Taiwan relations, regional security architecture, and economic partnerships across the Indo-Pacific. The discussion addressed key policy challenges including defense cooperation, trade relationships, and technological partnerships.

Feature

This past semester, the Rajawali Foundation Institute for Asia engaged in conversations and research on topics ranging from Indonesia’s election to US-Taiwan relations with the goal of continuing to develop policy solutions to the region’s most pressing concerns.

Essay

A summary of the event, co-hosted by the Rajawali Foundation Institute of Asia and the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

Video

As a new administration takes shape in Washington, join us for a timely discussion exploring the complex dynamics shaping the Indo-Pacific region. We will examine critical questions facing U.S.-Taiwan relations, regional security architecture, and economic partnerships across the Indo-Pacific. The discussion addressed key policy challenges including defense cooperation, trade relationships, and technological partnerships.

Feature

This past semester, the Rajawali Foundation Institute for Asia engaged in conversations and research on topics ranging from Indonesia’s election to US-Taiwan relations with the goal of continuing to develop policy solutions to the region’s most pressing concerns.