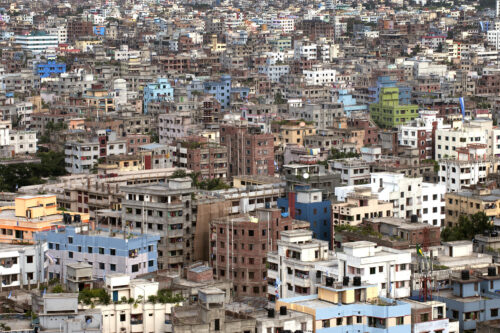

Since gaining independence in 1971, Bangladesh has been ascribed many labels. Once called a “bottomless basket” and the “most corrupt country in the world,” analysts, who now predict that the South Asian nation is on its way to becoming a trillion-dollar economy, often describe the country as an economic miracle.

According to Bangladesh Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen MC/MPA 1979, Bangladesh has every intention of building on its enviable economic growth trajectory and is working towards fully eradicating poverty, with a goal to become a high income country by 2041. Momen, who spoke at Harvard Kennedy School on Monday, March 21, at an event organized by the Rajawali Foundation Institute for Asia’s Bangladesh Public Administration Project, described how the country was able to halve poverty rates and boost economic growth over the past few decades.

“She says connectivity is productivity,” Momen noted before a group of faculty and students, referring to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who has led the country for most of the past two decades. To that end, Bangladesh has invested in the country’s physical infrastructure, but its government has also prioritized digital development and connectivity. From helping citizens purchase cell phones to digitizing passport applications, the country is continuing to look for opportunities to integrate technology.

In 2009, when the government called for Bangladesh to achieve food self-sufficiency by 2013, “many people didn’t believe it,” recalls Momen. But after subsidizing key agricultural inputs like fertilizer, and ensuring water reached farmers who needed it, agricultural productivity shot up.

As agricultural productivity grew, so did the country’s manufacturing capacity, especially its garment production. New jobs brought increasing numbers of women into the country’s workforce, but female employment alone was not the driver of growth. Momen highlighted the country’s investment in education and female leadership as essential to the country’s success.

“In order to increase the enrollment of female students, the government provided stipends and free books,” he says. Women have also been involved in the process of development at every level. Fifty seats in Bangladesh’s parliament are now reserved for women, with women eligible to compete for any of the 350 total seats.

Yet, despite the progress Bangladesh has achieved in the last few decades, climate change poses an existential risk for the country. A majority of Bangladesh sits below sea level. Climate change threatens much of Bangladesh’s agriculture, as rising sea levels increase water salinity, making once fertile areas unfarmable. Because of flooding, “each year, around 650,000 people are forced to move from their homes,” said Momen.

Though Bangladesh makes minimal contributions to total global greenhouse emissions, the country is committed to moving to renewable sources if they can access and afford them, says Momen. “We don’t have the technology; we don’t have the money. So, we are asking the global leadership to come up with the technology for renewable market and affordable financing,”

The country is also facing additional strain as the war in Ukraine drove up prices on things like fertilizer, food, and fuel. Bangladesh is currently subsidizing costs for low-income citizens but this strategy is not sustainable. “If the war continues for a longer time, we might not be able to do that. It could cause a big problem.”

Rising prices are an unwelcome reality for the country’s young graduates, many of whom are struggling to find a job. “Each year we get around 2 million newcomers onto the job market and we provide around 1.6 million jobs,” says Momen. The country has launched training programs but still needs to spur additional job growth.

Though all these challenges seem worrisome, Bangladesh is a country born out of adversity. “It’s a remarkable story of success against all odds,” said Tony Saich, director of the Rajawali Foundation Institute for Asia, who was moderating the discussion.

As Bangladesh looks to confront these issues and continue to grow, Momen reminded the audience of just how far the country has come. “That bottomless basket of 1970 now is vibrant; now it is the land of opportunity.”