Anyone who has dealt with the Chinese Communist Party ought to know that negotiation only truly begins after everyone has signed on the dotted line. According to the official position of the Central People’s Government, the Sino-British Joint Declaration is now merely a historical document with no current significance.

The key to Hong Kong’s success was never about democracy. After all, Hong Kong was not a democracy under British Colonial rule. However, Hongkongers had basic freedom. The freedom to be left alone by those in power. The freedom to make a living and to get on with life. The freedom to speak out or not to say anything. And that freedom was protected by the rule of law.

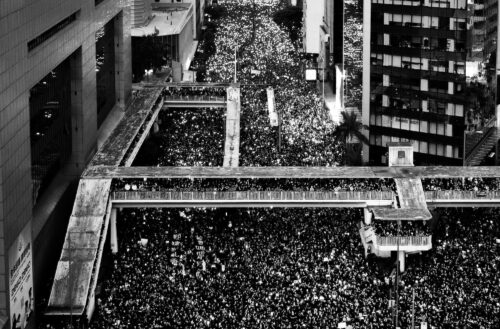

Many people escaped Communist China in the mid-20th century to find freedom for themselves and their families. They found what they were looking for in colonial Hong Kong. Decades later, those refugees would never have imagined that their children would need to fight to protect that freedom. From 2003 to 2019, millions of Hongkongers took to the streets on July 1st. The essence of their every chant was “Leave us alone.” The narrative now pushed by China is that the pro-democracy protests were somehow instigated by foreign forces. Should the international community care about what’s happening in Hong Kong? Absolutely. But it is ludicrous to suggest the protests movement were instigated by foreign powers. It was a cause led by the Hongkongers for Hong Kong’s freedom.

Freedom, alas, has now been sucked out of Hong Kong following the promulgation of the National Security Law. Every few months or so, the National People’s Congress issues its new edicts from Beijing, ruling Hong Kong as its colony from afar. Civil society has been completely dismantled, with the rule of law in tatters.

Hong Kong’s experience has taught us that freedom without democratic governance is ultimately unsustainable, and trusting those in power to act with restraint is futile. The city is now suffocating under authoritarian rule. Opposition figures, students, journalists, radio hosts, and civic activists are arrested daily or forced into exile. An international treaty has been torn up before the eyes of the international community. The Hong Kong story is consistent with the rest of the national policies now emanating from Beijing, including those on Taiwan, Xinjiang, the South China Sea, trade sanctions against Australia, or wolf-warrior diplomacy. Political considerations now trump all other considerations, economic ones included. The pragmatism once championed by earlier Chinese leaders must give way to China’s most powerful political ideology: Xi’s nationalism.

The inherent contradictions between Mainland China and Hong Kong’s ‘two systems’ have always existed, but they were painfully laid bare in 2020. The failure that lies beneath “One Country, Two Systems” is the fallacy in hoping that an authoritarian regime would trust its people to make decisions for themselves. If the world was naive back in 1997, it should be clear-eyed. Our Taiwanese friends have certainly taken note. The common law traditions once laid down by Wu and many others after him will soon be relegated to history as Hong Kong enters this ‘new’ era.