Written by Jérôme Doyon, China Public Policy Postdoctoral Fellow AY 2021-2023

A hundred years after its creation, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is one of the largest political organizations in the world, with about 95 million members. The party owes much of its resilience to its continued ability to attract new blood into its ranks. The organization has successfully reinvented itself after the economic reforms initiated in the late 1970s under Deng Xiaoping and remained appealing to young and educated Chinese despite no longer having a monopoly over social mobility. Yet despite the Xi Jinping administration’s endeavor to realize the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation,” current policies call into question the CCP’s ability to renew its ranks.

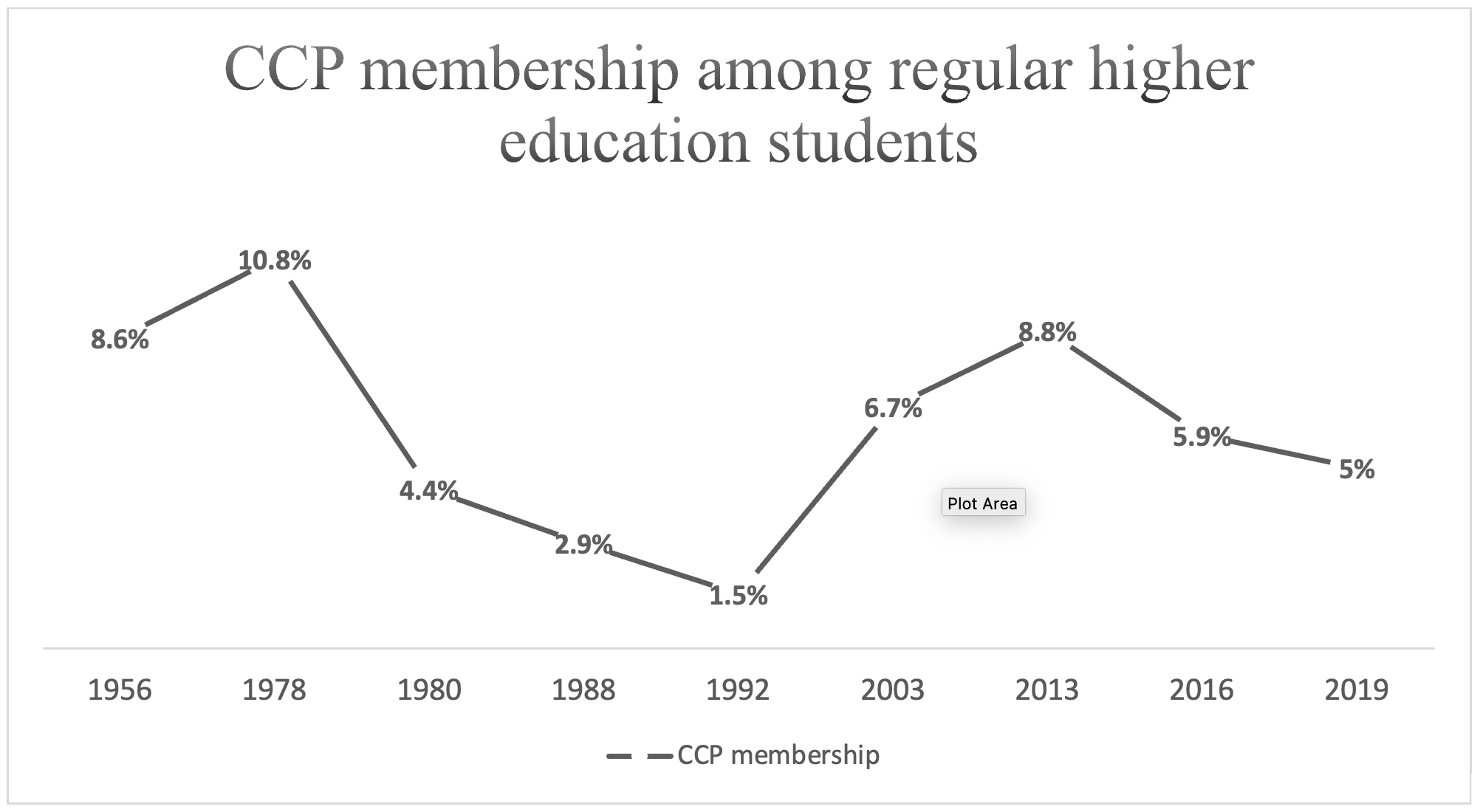

Today, young people represent about a quarter of the CCP’s total membership. But despite its growing membership, a close analysis of the CCP’s recruitment trends shows that it is attracting fewer young people. While the number of CCP members under 35 years old increased steadily from the 1990s until 2013, it decreased after Xi Jinping took power. This decrease is primarily due to the CCP’s diminishing presence among university students. The figure below illustrates this trend, tracing the ratio of university students who joined the party since the 1950s. The last time we saw a drop in students entering the party was at the beginning of the reform era, from 1978 up to the 1989 mobilizations. After repressing the movement, the CCP launched a massive recruitment drive among university students to ensure they had a stake in the regime’s survival. While the CCP managed to keep up with the rapid increase in university enrollment until 2013, the Xi administration appears less keen on co-opting students into the CCP.

This change coincides with a decrease in the membership of the Communist Youth League (CYL), the CCP’s leading youth organization that recruits young people between 14 and 28 years old. This is the first time since 1989 that the youth organization has seen a decrease in membership, going from 90 million youth in 2012 (when the CCP itself only had 85 million members) to 81 million in 2017—a loss of around 10% of its membership in five years. For comparison, the CYL lost 4 million members (about 7% of its membership) just before the Tiananmen movement, between 1987 and 1989. Interestingly, the Chinese party-state stopped publishing CYL membership numbers after 2017, probably to hide further decline.

Xi Jinping’s negative assessment of the Youth League’s work led to a change in its recruitment policy, favoring activism over having large numbers of passive members. He warned the CYL against ’empty slogans’ and the risk of becoming an ’empty shell’, viewing it as increasingly removed from the vanguard ideological and mobilizational organization it was supposed to be. Yet the CYL is a critical recruiting channel for the party. Since the 1980s, CCP recruits under 28 first join the CYL and are then recommended for party membership by their League units. Providing fewer reserve members to the CCP could lead to an aging party in the mid to long term.

Xi Jinping is also undoing past policies regarding the recruitment of party-state officials, which impacts its ability to renew its leadership. After Deng Xiaoping called for the rejuvenation of the cadres corps in 1980, the party-state implemented new recruitment and promotion rules, including the establishment of a retirement system as well as a complex structure of age limits affecting appointments at all levels of the polity. The PRC became the only Leninist regime to develop such a strict system of age rules, facilitating the recruitment of young and educated cadres. But Xi has been progressively rolling back this age-based system. Since 2014, documents on the recruitment of leading officials note that age limits should be “implemented with flexibility.” Similar language was used regarding the selection of Central Committee members ahead of the 19th Party Congress in 2017, leading to the oldest Central Committee in decades, with an average age of 57, compared to 53 ten years earlier.

This is only the beginning of a trend, as the CCP, and state employment, remain highly attractive to young Chinese. In fact, the turnout for the civil service exam is higher than ever due to the appeal of stable employment during the current crisis. Yet, by limiting avenues of rejuvenation, it could become increasingly challenging for the party-state to attract educated, young Chinese candidates, and the system risks becoming a gerontocracy.